Researchers Aaron Hermann and Hussain G. Rammal from the University of Adelaide argue in their paper ‘The grounding of the “flying bank”‘ (2010) that a major factor contributing to the demise of Swissair was bad strategic decision making resulting from groupthink.

Let us have a closer look at what groupthink is and what companies can do to prevent it.

Causes and Results of Groupthink

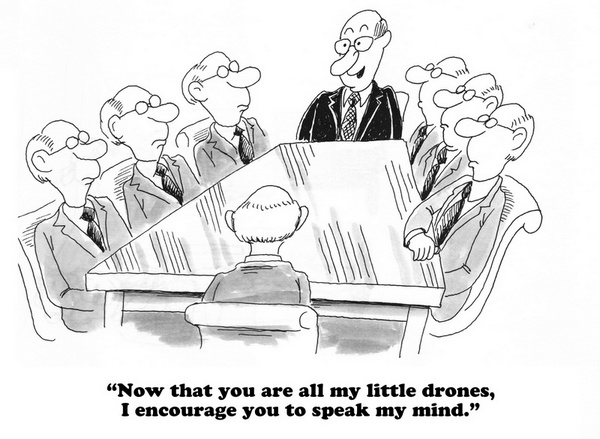

Groupthink happens, when a group of people jointly makes worse decisions than each group member would have done on their own. The causes for this irrational behaviour are based on group dynamics driven by mutual pressure for homogeneity and conformance to real or perceived group values as well as a hierarchical group structure where the leader is always right and everyone else conforms quickly to what he said he wants or what they guess he might want.

The economic cost of bad decisions based on groupthink can be enormous, as examples from Enron to Swissair and more recently Volkswagen show. Allowing groupthink to happen when high-stake decisions are taken is completely unacceptable, as the methods for avoiding groupthink have been known for at least four decades. Irving Janis, the research psychologist from Yale University who first explored the phenomenon scientifically, already presented a number of useful methods in his book “Victims of Groupthink”, first published in 1972.

How to Prevent Groupthink

There are three methods that I consider best for preventing groupthink. They are simple, but no always easy to implement. Here they are:

Method 1: Diversity of Minds

Homogeneity of group members in terms of their professional background and corporate socialisation is usually favouring groupthink. It usually does not make a big difference, if you have ethnic and gender diversity in a group. People who have been exposed to the same corporate culture on a similar hierarchical level for a long time will typically have a tendency to converge in their thinking.

Thus, for making important corporate decisions, it is advisable to foster the diversity of minds by including some people with contrarian views and different career paths in the process. If you pick someone from a lower hierarchical level than the rest of the group, it is important to make sure that power differences between members are irrelevant in the discussion, which should focus on the subject and the merits of different arguments.

Method 2: Effective Facilitation

In order to achieve a free flow of arguments and an open discussion uninhibited by considerations of hierarchical power and departmental interests, it is important to have an unbiased facilitator who neutrally enforces the rules like a referee in football.

What happens quite often is that the CEO is chairing the meeting. Apart from the fact that he is already the most powerful person in the room, his role is further strengthened by the fact that he can steer the discussion in whatever direction he likes. Ideally, the facilitator should be an executive who is well-respected by his peers and who is adequately trained in group facilitation, or alternatively an external professional facilitator who has the authority to lead a meeting of senior executives.

Method 3: A Devil’s Advocate

Methods 1 and 2 might already do the job. However, there could still be a risk that participants avoid a controversial discussion and converge too quickly on a decision before they have properly explored a number of options. It is thus advisable to include a devil’s advocate in the discussion. His main job is to challenge assumptions, detect weaknesses in the majority-supported option, and defend unconventional options.

Ideally, the devil’s advocate should be an external facilitator or coach who has no personal stake in the decision and who is well versed in group dynamics and decision making processes. The devil’s advocate should not dominate the discussion, but just give impulses to the discussion when everyone else is converging too quickly on a certain option without sufficiently exploring all relevant options.

Conclusion

Groupthink is a major scourge of executive boards and supervisory boards. The three recommended methods can help avoid groupthink and enable a higher quality of executive decisions in companies of all sizes. Consider hiring an external facilitator and an external devil’s advocate for meetings on major strategic decisions. Apart from reducing the risk of groupthink it would also help avoid organisational blindness.